International Astronomy and Astrophysics Competition

A career in science means competition and collaboration almost equally. In a digitally-connected world, research is a global affair, most of the times. Here's a competition for young students which showcases the value of a community, and makes an effort to challenge them to read research papers.

If the Sun were the size of a football, how big would the Earth be? What makes a comet and how does its luminous tail appear? What gravitational pull does a 30-ton truck generate?

Astronomy and astrophysics draw curious minds of all ages. It's almost impossible you haven't heard of at least one of Stephen Hawking, Roger Penrose, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Brian Cox, or read about past and future space missions, or the present race for space (re)kindled by SpaceX.

Science-fiction literature and many popular video games also feature "space", with lots of creativity, which sends you into "a galaxy far far away" aboard a spaceship in a mission to save the world.

The immense Universe and extra-terrestrial phenomena have sparked curiosity of thinkers and researchers since ancient times. The Universe was practically the first model of infinity, as well as the house of the god(s).

When science began to modernize, astronomical observations helped improve optical technology and provided predictions based on mathematics. The geocentric and the heliocentric models were the heart of some of the most heated debates in the history of science. Who doesn't know Galileo's words, Eppur si muove… (And yet, it moves…), referring to the Earth's rotation around the Sun, which he uttered even facing a condemnation?

If you're a student and want to learn more about astronomy and astrophysics, more than the law of universal gravitation, the Astronomy and Astrophysics Olympiad could be a good opportunity to test your skills.

But there are more challenges to test yourself and furthermore, contribute to preparing others in the field you're interested in.

The International Competition of Astronomy and Astrophysics, organized by the German association Edu Harbour proposes a friendlier format but it also includes tasks that differ significantly from those you may find in school or even in other international competitions or Olympiads.

One of their missions is to make science in general and astronomy and astrophysics in particular accessible to everyone. You only have to have an Internet connection, download the problems, solve and upload them – at least for the first two rounds.

The third and final round entails a video recorded evaluation, but you can record yourself, you don't have to go to a specialized examination center. And if you finish on the podium, the prizes include a telescope, autographed by two Nobel laureates (Gerard 't Hooft and François Englert), as well as the astronaut Frank De Winne.

All three rounds of the competition contain problems that are a unique and welcome combination of mathematical computations, understanding of phenomena, of research or lab tools, as well as research papers.

For example, in the qualifying round (the first), you may be asked about the parts of a telescope. Another question is the one I've selected in the introduction of this article, about the comet.

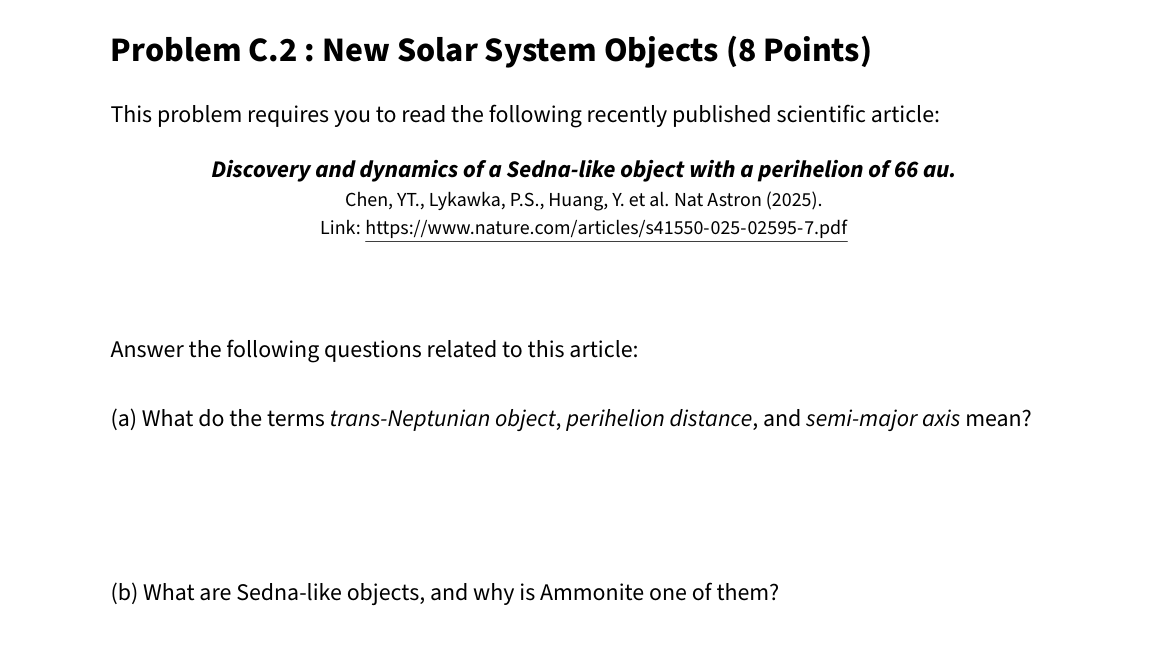

In the second round, the problems become more difficult, but also more challenging from a mathematical point of view. But the most remarkable feature is that the last two subjects give you two research papers to read. You're given links to two recent, open-access articles, which you must read and study. Then follow some questions based on them, some requiring small computations, but most are qualitative and explanatory.

Such a challenge greatly improves scientific literacy for all participants. Furthermore, it also shows that research papers are not necessarily hard to understand, overly complicated and impossible to understand without a PhD. degree.

The first two rounds don't have a limited time for solutions, at least not in the way you're probably used to. They are like take-home exams: you download the subjects, solve them, then upload them in a matter of days or weeks. All that matters is that you do it before the deadline, which could mean up to two months.

The final round has a stricter approach, with twenty multiple-choice questions to solve in twenty minutes. Among them, you could find some computations, but also general questions such as:

- What is the most present chemical element in the Universe?

- What planet has the greatest rotation speed?

- What does "perihelic distance" mean?

If you're really passionate, you are encouraged to become an ambassador of the competition and help spread the word. I'm happy to be working at Poligon Educational with a student who's a contestant and an ambassador in Bucharest, Romania: Cristina Milutinovici. Students and teachers can reach out to her for more information at crimilutinovici@amb.iaac.space.

I should also add that there are sister-competitions of IAAC in linguistics, in computer science, in general physics, and in mathematics – the latter containing many geometry and number theory challenges.

Scientific education and literacy, as well as the experience of an international community are values that I think everyone working or interested in education should promote. Most of us feel the impulse to share what we love and create a group of people with common interests. It was one of the premises that prompted me to start The Gradient and I think that a competition such as IAAC teaches young people to become a part of a community more than a contestant, which fits my convictions perfectly.

Thank you for reading The Gradient! The articles here will always be free. If you've read something useful or enjoy what we publish, please consider a small contribution by sharing on social media, starting a paid subscription, or a tip.