Math to the Power of Nibs: Researchers’ Fountain Pens

Among pencils preferred by artists and ballpoint pens that just do their job, fountain pens have a special place in history. We may not know how many theorems were written with them, but there are some well documented connections between mathematicians and their fountain pens.

“A mathematician is a device for turning coffee into theorems”, said the Hungarian researcher Alfréd Rényi.

The typical picture is that of the teacher or keynote speaker, holding a piece of chalk in their hand, in front of a blackboard that’s filled with formulas, definitions, theorems, and the occasional geometric picture or sophisticated diagram. In their other natural habitat, mathematicians can be found in their office surrounded by or even buried under papers, each filled in various degrees with formulas, theorems, or diagrams, written and erased with pencils, or scribbled and scrawled with the first ballpoint they laid their hands upon. For several decades, the image includes computers, but pens, pencils, and paper are far from gone.

Many researchers say that mathematics takes shape on paper, with a pencil or a pen that faithfully follows the flow of thoughts. Handwriting in general has this merit of intentionally slowing down one’s thoughts, thus improving attention, understanding, and memorization.

But it’s not the tool that produces the result, it’s the user. At the same time, you probably know writing habits, what pens, typewriter, or software your favorite writer uses. It’s the same with painters, where one hardly resists buying the very paper that Dalí used or watercolors that are named by Dürer.

Apparently, mathematicians rarely develop passions for notebooks, pens, pencils, or ink ― or at least they rarely express such interests, compared with writers. There are fascinating examples of hoarding a type of chalk that many professors adore, but they are rather the exception than the norm. Mathematicians usually work with what comes to hand and one can bet that they will find a mug with pencils and Bic Cristal ballpoint pens in almost any office.

Pencils, Fountain Pens, Ballpoints: A Brief History

The graphite pencil was the first modern writing tool, invented in 1795, by the Frenchman Nicholas-Jean Conte. The main technical issue had been to have a graphite lead encased in a block of wood, because otherwise, the mixture of graphite powder with hardening agents was known and used since the 1600s. But for many years, the pencil was mainly a tool for artists or craftsmen like carpenters. The very etymology of the word, pencil, comes from the Latin penicillus, which means “small tail”, related to a fine brush. The French original word, crayon, is related to the French craie, which means chalk, referring to the common origin of chalk, pencils, and perhaps charcoal.

Feathers, dip pens, or bamboo sticks were the popular writing instruments until the invention of the fountain pen, by the Romanian Petrache Poenaru, in 1827. Several decades later, the device had spread especially in Europe, through companies like Pelikan (founded in 1838), Waterman (1884), Parker (1888), Kaweco (1889), Conway Stewart (1905), or Montblanc (1906).

The design had evolved, and ink leaks were much rarer, once the barrel was better sealed and the ink flow to the nib was improved. A short history of fountain pen manufacturers, as well as particularities of each model, are described by Peter Twydle in a book that I recommend to curious and enthusiastic fellow pen fans.

The patent for the ballpoint pen was given in 1888 to the American John J. Loud, but commercial success came much later. The Hungarian journalist László Biró grew annoyed by the time required to refill fountain pens, the long ink drying times and the occasional leaks, so he worked with his brother, who was a good chemist. Their objectives were clear: to develop a more viscous ink to dry quicker, a reservoir to last longer, and a suitable nib, for which they added a small rolling ball at the tip. The invention was presented in 1931 in Budapest, and it became such a huge success, so much so that in some countries ballpoints are still called “biros”.

Writing Remains. What About the Pens?

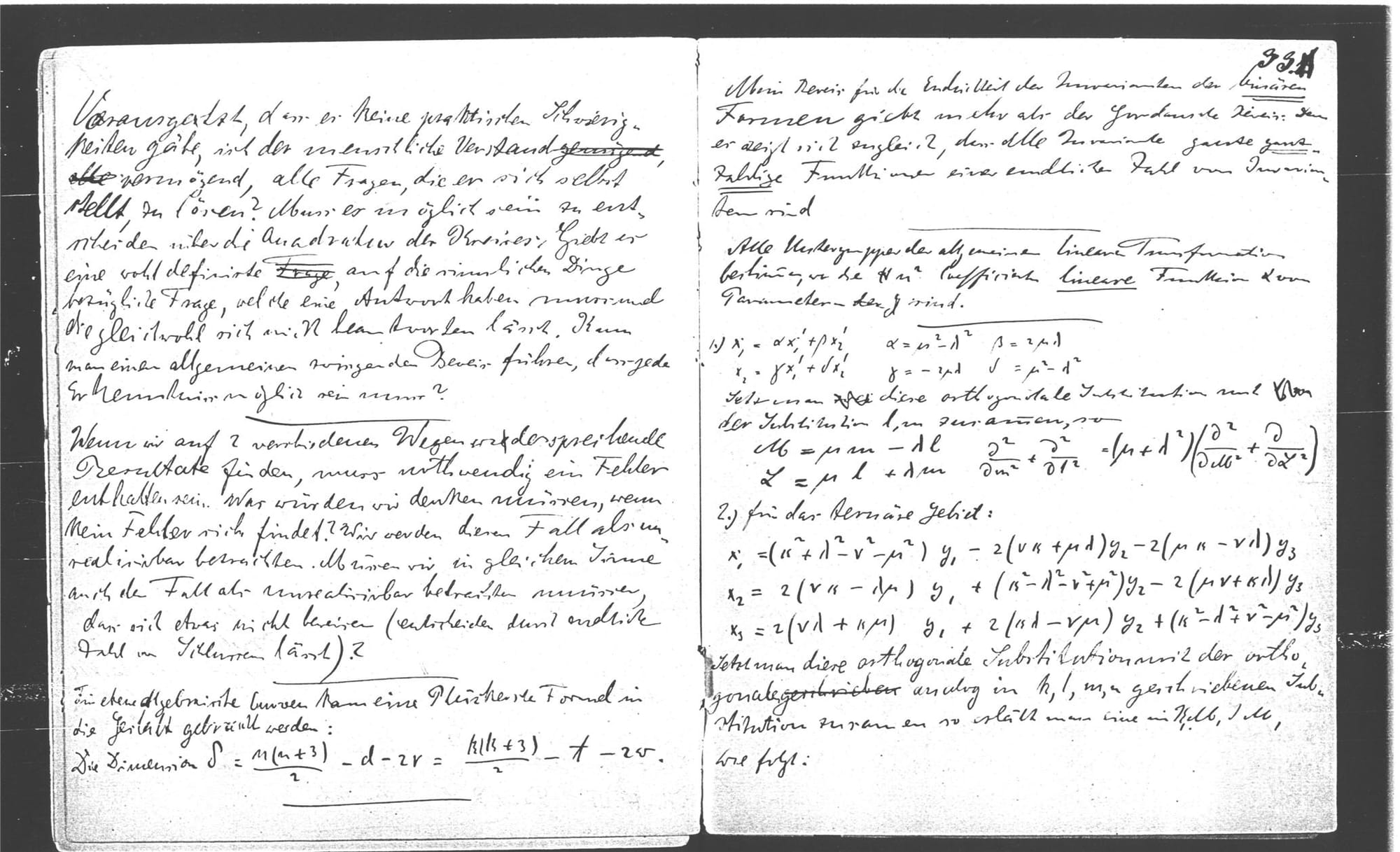

The historical challenge of tracking mathematicians using fountain pens is surprisingly hard. Except for the rare cases when a researcher was photographed with their pen in hand or on the desk or the even rarer occasions when they wrote in a diary or a letter about such preferences, the connections that historians made are mostly based on archival analysis.

Before becoming widespread goods that were exported, fountain pens were sold to local markets. Most schools used them, and many still do, under the assumption that they improve calligraphy and hand grip. As such, there were many pens throughout the years that emphasized finger comfort. One of the most famous is the triangular grip found in Lamy fountain pens, especially in their ABC model, designed for school children.

Nowadays, popularity is decreasing, but several decades ago, one could bet that all school children were educated to use fountain pens. Despite obvious advantages of ballpoints, the momentum of a century that had passed since Poenaru’s invention and Biró’s made fountain pens almost irreplaceable in schools.

Since many mathematicians worked in academia, in universities, or schools, they always had fountain pens on their desks, and most of them were local brands.

Graphologists, archivists, and historians also found proof in expert analysis of ink traces on paper. Many inks had specific formulas of precise chemical components, such as iron gall (which is still used in archival ink), and there was not much variation in color. A similar argument works for nibs, since grinds were not very diverse, but each brand had its technique. That’s why experts could deduce, with reasonable probability, the type of pen and ink in some manuscripts. The inventory of the estate of a defunct mathematician could also be used as proof, since one could say that if a fountain pen was found on one mathematician’s desk or among their possessions and it was not sealed or brand new, then they could have used them.

Few Verifiable Examples

Such introduction and precautions out of the way, here is a clear example: the late mathematician Nick Higham. In a post on his personal blog, he wrote about his preference for inks, but not specific pen brands. Previously, he had written about pencils, but then he steered towards fountain pens.

His preferred inks were made by Noodlers, an American brand, that is known for high intensity pigments and quick drying times. Moreover, Higham used various colors of ink for specific tasks. He used to grade paper with red, or orange ink made by Waterman, annotated research materials or books with Pilot Iroshizuku inks, and used Diamine for his all-purpose writing (Asa Blue, Oxford Blue, and Red Dragon).

Going further, the scarcity of available information leads me astray so the examples that follow are well documented but not strictly of mathematicians.

Albert Einstein’s fountain pens were made mostly by Waterman, Pelikan (model 100), and Montblanc. The online community on the forum Fountain Pen Network discusses such details. One of his pens was the Waterman Ideal 22, which can be seen in the Boerhaave Museum in Leiden. Einstein received it as a gift in 1921 from the physicist Paul Ehrenfest and we know for certain that he used it when drafting the general relativity theory.

Also coming from physics, but from the present, is Neil deGrasse Tyson. In an interview from 2017, Tyson displays his collection, most instruments being made by Montblanc, given his preference for larger pens, like the model 149.

The same pen was among the favorites of Edsger W. Dijkstra, one of the most important theoretical computer scientists. Renowned for his impeccable calligraphy, and also for the lack of references in his articles, Dijkstra used many fountain pens, which he discusses in this interview. Being rather theoretically minded, Dijkstra never wrote his articles on a computer. In the obituary that Krzysztof R. Apt published in 2002, it is written that Dijkstra used typewriters and fountain pens, usually by Montblanc.

Speculations and Possibilities

The rest of the examples I came upon are not as solidly supported by evidence as the rest and rely mostly on associations and speculations. For example, the British mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) could have used fountain pens made by Conway Stewart or Onoto, both companies being founded in 1905. We know for sure that the former Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill was a client of both companies, so there is a chance that Russell could also have owned such pens.

In Conway Stewart’s catalogue of clients, one could possibly find Alan Turing as well. A preprint from 2012 shows that Turing had a fountain pen called “Research”, which was gifted in 1932 by Chris Morcom’s mother and sadly lost by the mathematician. The nibmeister Richard Binder writes that the generically called “Research” pen is very likely to be the model patented by Alexander Munro in 1916.

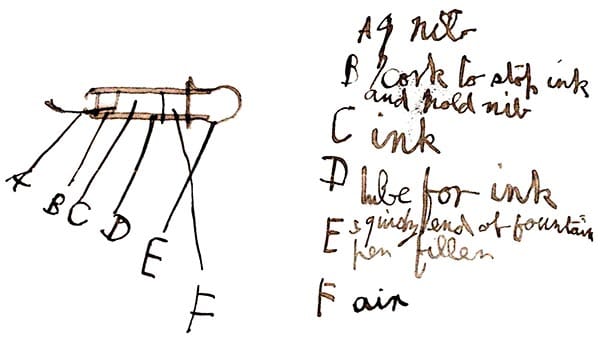

Turing was passionate about fountain pens and inventions since childhood. During his school years, since he was 10-14 years old, he designed his own fountain pen which had a rubber end like a medicine dropper, and the nib seal was made of cork.

Recently, Conway Stewart dedicated two fountain pens to Alan Turing, which can be bought from the National Computing Museum in Bletchley Park ― the former HQ of the cryptography group during World War II. They released a limited edition, with 251 pieces, and another one that celebrates Turing’s collaboration with Gordon Welchman. Both have intricate details that represent Turing’s work on the Enigma machine.

Another direct example, but quite imprecise, is that of Kurt Gödel’s letters to his mother and family. For example, in a note dated 1949 he writes:

P.S. My poor handwriting is explained due to the loss of my fountain pen and the new one is not worth anything since I wanted to be frugal and bought myself one for $1.50. I lose my fountain pens from time to time and then am annoyed if they were expensive.

We don’t know the model that the Austrian used, but correlating his life with the German market would suggest either the Pelikan 100 model, sold between 1929 and 1944, or the newer model (100N), available from 1937 to 1954.

In other letters, Gödel thanks his mother who sent him books, accessories, and fountain pens, but in the 1940s, the packages were often checked by the Nazis, and not all reached their destination.

In 1954, Gödel writes to his mother, from the USA, glad that he could send a new fountain pen: “It is a new kind of fountain pen that sucks up the ink via a nozzle.” he writes. A historical analysis suggests that it could have been the Sheaffer Snorkel pen, an American brand which produced this design from 1952 to 1959. It features a metal rod like a straw that is lowered through the nib to suck ink in the barrel.

We fountain pen enthusiasts appreciate such details and gimmicks. We love variety in terms of nibs, filling mechanisms, ink colors, or paper properties. But beyond such material details, we appreciate the experience of writing with a fountain pen. The slowness that it imposes, the tactile feeling of friction between the nib and paper, the traces of ink that dries under our eyes, the line variation, and not least emptying and refilling the reservoir.

Beyond being a writing instrument, a fountain pen is one of the most personal items that one could own. Handwriting will not become extinct if there are still people pouring their minds and souls into ink, through a link as direct as there could be.

We may not know how many researchers shared this passion, how many used fountain pens for lack of a better alternative, or treated them like simple tools. There’s no doubt that their theorems would have shined the same light even if they scratched them with their fingernails on the walls, or they wrote them in pencil, or they dictated them. But I like to believe that for almost 200 years, fountain pens have been connecting minds and souls looking for a deliberate slowness, to savor the moment of creation and paying attention to their marks.

Thank you for reading The Gradient! The articles here will always be free. If you've read something useful or enjoy what we publish, please consider a small contribution by sharing on social media, starting a paid subscription, or a tip.