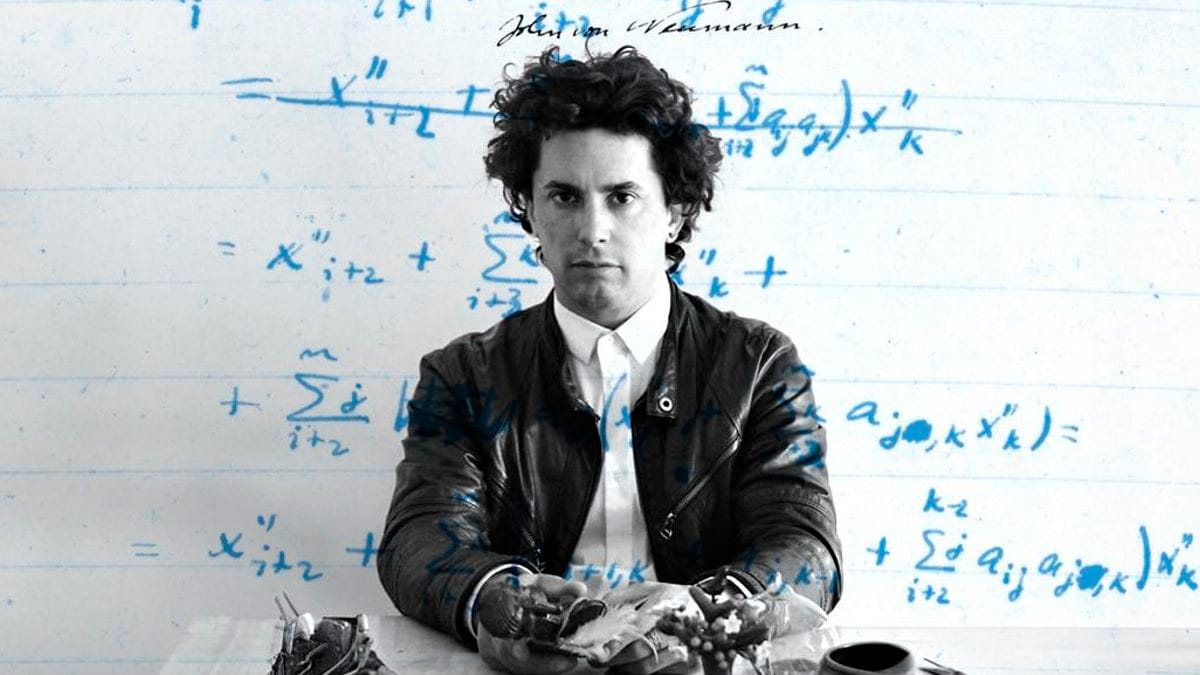

Benjamín Labatut: When we cease to understand the world of a MANIAC

Fictionalized biographies of great researchers explain through metaphors and symbols the amplitude of their work. Chilean writer Benjamín Labatut’s novels argue that the most powerful impact is on the minds of those luminaries.

The Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann has a distinct reputation. His research results have influenced mathematics, physics, and computer science, but they did it through constructions and theorems of such depth that they are almost incomprehensible when you first study the topics. Thus, it may well be the case that Johnny (how he liked to be called after moving to the US) appears only after you’ve established a good foundation of learning, beyond immediate preliminaries. Mathematicians know him from algebra, analysis, and game theory. Physicists connect him to his 1932 treatise, Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (written in German!), where he insists on understanding the concept of measurement. Therefore, von Neumann appears not as a popular researcher like Pythagoras or Einstein, but once you read his biography and study his results, you immediately know he was one of the greatest. Even when you only associate him with MANIAC, the acronym for the first computer he designed and used.

That could be a reason why Benjamín Labatut’s book, titled precisely “The MANIAC” and published in 2023, seems like a niche story. It evolves around advanced quantum physics concepts and their interpretation. In the first years of this new paradigm of thought in science, the mathematical foundations, the experimental results, and the natural, more intuitive interpretations, to the extent that they were still possible, were all equally important. Von Neumann’s 1932 monograph tries to do just that. He asks what remains of the concept and procedure of measurement at the subatomic level and how it relates to computation. Since one can no longer see subatomic particles to directly measure their behavior or observable quantities, computation is a plausible substitute. But does computation still reflect the instantaneous, spontaneous nature of a physical system? Such questions were at the core of the so-called Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, named after the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, one of the most important researchers in the foundations of quantum mechanics. Among his and von Neumann’s collaborators, direct or indirect, were Paul Ehrenfest, Eugene Wigner, or Richard Feynman, all of whom are present in Benjamín Labatut’s work.

The Rotterdam-born Chilean author said in an interview that all output of a writer is fictional. He does ample amounts of research, with advanced scientific treaties, but he would like to be seen by readers as a creator of stories and characters, even if many of them have varying amounts of intersection with historical reality.

The title he gave to this novel, “The MANIAC”, means much more than von Neumann’s computer prototype. Labatut is fascinated by the borders of thought, pushed beyond its limits. His books always have at least one character inspired by a person who history remembers as a genius, but the fictional variant that the author proposes contains many psychopathological details. Such a turn is not disrespectful, but it emphasizes the dedication that some researchers put into their work to the point of total immersion, when they offer their full mental capacity to their pursuit.

“The MANIAC” contains three parts. The first starts with Paul Ehrenfest, with his mind shattered, who decides to kill his son (born with the Down syndrome), and then himself. The second part shows von Neumann’s contributions to the development of quantum physics, but everything evolves over the background of the Manhattan Project, which was known since the beginning as a serious threat to the future of mankind. The third part, which is completely separated from the rest, reaches the present and speaks about artificial intelligence, including a long essay on AlphaGo, the first robot which consistently beat a world champion at the game of Go.

A similar structure can be found in his 2020 book, originally titled “Un verdor terrible” (“A Terrible Greenness”), translated in English as “When We Cease to Understand the World”. It is no longer centered around a single researcher, and instead it contains many episodes which are partially connected at times.

The disturbing elements are present here as well. The original (Spanish) title refers to the first story, which tells about Fritz Haber’s creation of pesticides and fertilizers. However, their morbid application was in the hands of the Nazis under the form of Zyklon B, the poisonous gas from the Holocaust.

Greenness, however, is Haber’s nightmare, when he deliriously imagines a world covered in plants, to the point of suffocation. This first story, which gives the title to the book, contains multiple scientific and symbolic meanings of colors, especially green and blue. The shades are connected to life, but they become symbols of death, through the traces and stains that cyanide-based poison leaves on flesh and objects.

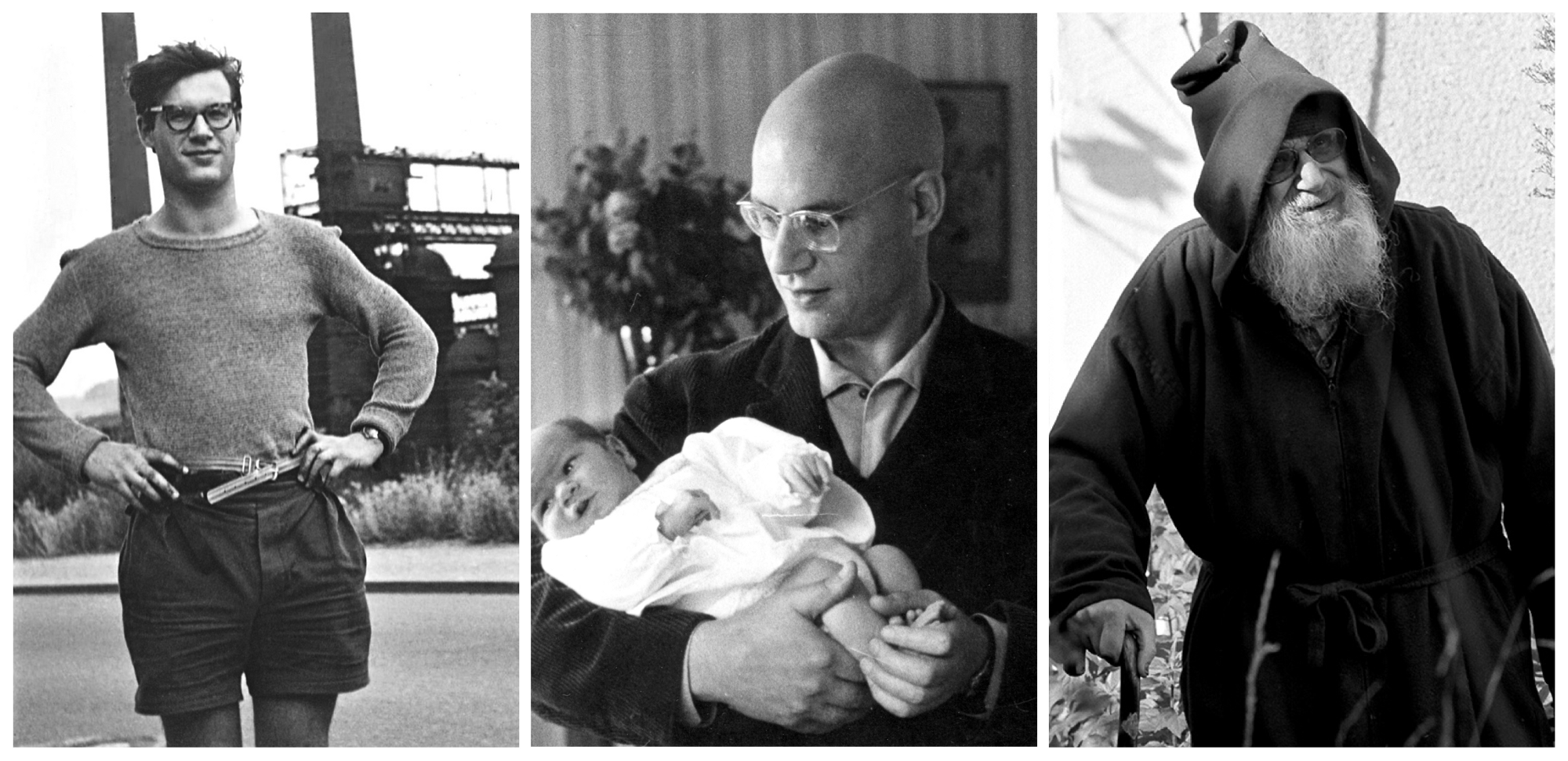

The other stories feature mathematicians (Alexander Grothendieck, Shinichi Mochizuki), and physicists (Karl Schwartzschild, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger), all absorbed by their pursuits to the point of losing their minds and arguably over that threshold.

Once again, greenness makes a gloomy appearance, this time in Grothendieck’s life. Secluded from public life and having renounced mathematics, he led a life of a vegetarian hermit, taking care of plants which webbed all through his yard and home.

“The MANIAC” is clearly a work of fiction, since von Neumann and his fellow physicists’ image clearly contains supernatural image. But Labatut said multiple times that “Un verdor terrible” contains only one phrase that’s completely fictional, while the rest are based on true facts. I find that hard to believe, but at the same time, literature has its own definition of truth, specific to the world it creates. Factual truth is rarely relevant, and instead, a likeness to reality is preferred, a verisimilitude.

In a discussion from December 2024, Labatut explains to the physicist Brian Greene:

“I’m interested in the moment when the mind breaks. When it goes too far. When it touches something it cannot understand and begins to unravel. […] I write about scientists not because of their discoveries, but because of what those discoveries do to them. The way they change, the way they suffer, the way they lose themselves. […] The most terrifying thing is not the bomb, not the AI, not the equations. It’s the mind that creates them. That’s the real abyss.”

In a way, Benjamín Labatut echoes Nietzsche: “if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you” (Beyond Good and Evil, 1886). However, even if the subject of the deranged genius is old and presented in multiple forms by many authors throughout centuries, I think that the Chilean’s novels have a distinct intensity. In them, the theme punches through centuries, with Ehrenfest, von Neumann and Hassabis in one instance, and Haber, Heisenberg, and Grothendieck in the other. The stories also transcend the individual (in the Manhattan Project), and the human (in AlphaGo).

When I think about the present, in which we see and experience the evolution and consequences of the discoveries made by the people Labatut wrote about, I can call his stories “fiction”, just like he advocates. But I cannot refrain from seeing it as a cautious warning, an abyss which is still far, but it does watch us all.

Thank you for reading The Gradient! The articles here will always be free. If you've read something useful or enjoy what we publish, please consider a small contribution by sharing on social media, starting a paid subscription, or a tip.