The Crest of the Peacock: Enumerable, Uncountable, and Infinite in Ancient India

Ancient Western spirituality and popular wisdom contain many numbers that have magical or symbolic meaning, such as 3, 5, 7, or 9. Indian scriptures of antiquity, however, are much more daring and precise. Would you believe in precisely 8,400,000 reincarnations?

The concept of infinity, one of the oldest and most profound in the history of ideas, was understood from the beginning as an upper bound that is practically unattainable but idealized. One reaches infinity by counting, or more generally, by increasing a quantity, or traversing a distance with no endpoint, since any presumably final step is a contradiction with respect to in-finiteness.

Many modern studies of neuroscience and psychology of education show that this is how the concept is most naturally understood: through the method of induction, to use its mathematical name. It starts with a small quantity, to which you keep adding, while making sure that any step you take, one more is possible. The transition from an arbitrary step to the next is the core idea of infinity, as a limit result of the process of induction.

The threshold between finite and infinite or innumerable is a question that many civilizations answer differently. For example, a book by the mathematician John D. Barrow (which I’ve recommended here) tells about the Botocudo tribe from South America. Their members pass almost immediately to the “uncountable” (practically infinite), because they didn’t need special words or applications for numbers greater than the total finger and toe count. Similarly, in Ancient Greece, you rarely find arithmetic that uses numbers greater than a few hundreds. The Pythagoreans were famous for their worshipping of numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and their sum, 10, while one of the founding fathers of arithmetic, Diophantus of Alexandria, worked with equations that had solutions ranging in the hundreds.

Things change quickly when you read about ancient Indian mathematics. Many of their holy or secular wisdom books contain explicit mentions of numbers of the order of millions or billions. Such numbers are not just named, but the Indian people operated with such quantities.

A cultural metaphor of India, which connects wisdom and knowledge to mathematics, is that of the peacock. Vedang Jyotish, one of the first astrology books, dated around 1200 BCE, gives a characterization of mathematics as the crest of a peacock. It thrones over the rest of the disciplines, but as a hidden gem. For a peacock, one first sees its large spreading tail, but the crest is, literally and figuratively, its peak. This was the inspiration for George G. Joseph’s book, which I recommend in the References.

Divine and Human Diversity of Infinity

In most cultures of the world, infinity is commonly associated with the Universe and Divinity, which was the case for the Indians as well. One of the first mentions of infinity is found in Mahābhārata, a collection of writings spanning from the third century BCE to the fourth century CE. Vishnu Sahasranama, a hymn dedicated to the god Vishnu, contains a mention of his 1000 names, among which there is Ananta, translated as “endless” or “limitless”.

But Ananta is just one of the many flavors of infinity in Indian culture. The holy books contain the four categories of being, three of which have direct references to infinity. Ananta marks a beginning with no end (some cosmogonies mention Vishnu’s birth). Then, Nitya is the category of those with no beginning and no end, Anitya names those with beginning and end, and finally, Anadi has no beginning, but it does end.

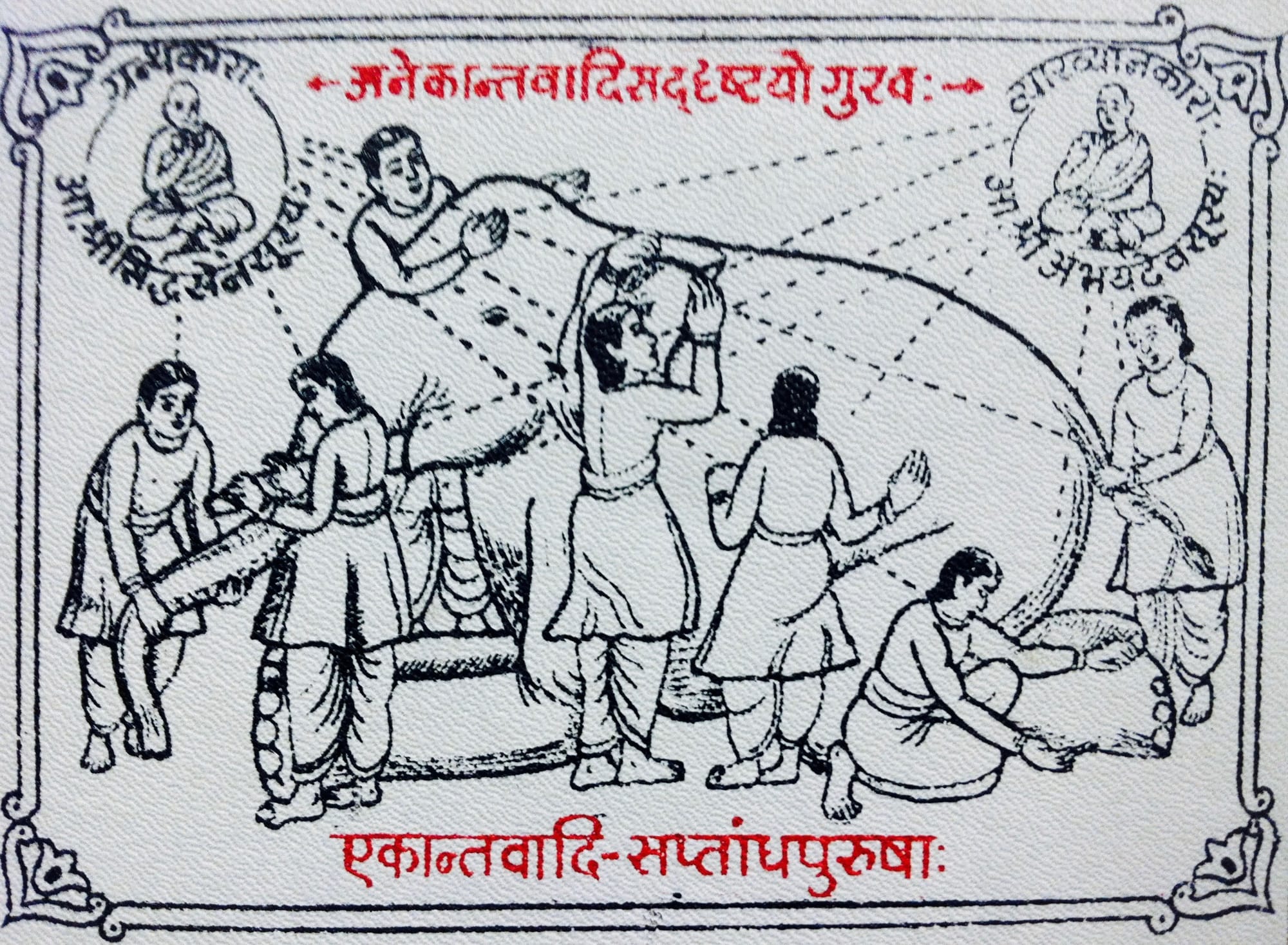

There’s a very impressive approach to infinity and large numbers in one of the most important religions and philosophies of India, Jainism. Some historical data connects the founding of this religion to Mahavira, who lived in the sixth century BCE and was contemporary with the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama).

Jaina books mention the attributes of the human soul, all of which are connected to infinity:

- Ananta-gyana or limitless knowledge.

- Ananta-darshana, which is limitless perception, through senses.

- Ananta-caritra, or unending consciousness, which connects the being to all forms of existence in the world.

- Ananta-sukha or infinite peace.

Seen through European philosophies, Jaina and Hindu spirituality have an atomist core. For example, in one of the most important commentary books of Jaina scriptures, Tattvārthasūtra, compiled between the second and fifth centuries CE by a monk (Acharya) called Umaswami, souls are made of parts, an uncountable quantity of “soul units”. Similarly, space contains an infinite number of “space units”, and a piece of matter, regardless of its size, could contain a finite, infinite, or uncountable “matter units” (which could be called atoms in Western terminology).

The Arithmetic of the Jaina Universe

To the best of my knowledge, Jaina mentions of large numbers in holy or secular wisdom books are unique in the history of philosophical and religious ideas.

They separated numbers into three categories: enumerable, uncountable, and infinite. The distinctions are not clearly explained, but one can imagine that enumerable numbers where those which one could find in everyday situations, while the uncountable could be referring to cosmic or divine proportions.

The infinite quantities are further divided in five categories: infinite in one direction (like the Ananta category, which has a beginning, but no end), infinite bilaterally (like Nitya), infinite in area or spatial spread, “everywhere infinite”, also connected to space, and perpetual infinity, referring to time.

Some huge finite numbers are precisely specified. For example, the cycle of life contains many rebirths, which are expected to span aeons. But the scriptures are precise: the usual number of rebirths is 8,400,000, except for some luminaries (called Jina), which could attain spiritual freedom (mokṣa) quicker. One of the founding fathers of Jaina, Jina Mahavira, is said to have needed only 27 rebirths until his liberation.

In Jaina scriptures there’s a unit for measuring time, called shirsa prahelika. Based on astronomical computations, filled with spiritual teachings, it is known to be the precise and impressively large number:

1 shirsa prahelika = 756 × 1011 × (8.400.000)28 days

A subdivision of this unit is purvis, which equals 756 × 1011 days, so 1 shirsa prahelika is (8.400.000)28 purvis.

The modern meaning of the word prahelika is that of “riddle”, sometimes in verse, but also beauty and progress. The historical link suggests that this immense quantity, the shirsa prahelika, could have been part of folk wisdom, perhaps specific to those who created mathematical riddles, like Diophantus of Alexandria.

Holy books speak about the immensity of the world but again through precise computations. They allow for a god to travel for six months such that every time they blinked, they covered approximately 12,000 kilometers. As expected, the Jaina don’t speak “approximately”: that number of kilometers is written as “a thousand yojana”. This is an ancient unit in India, Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar, whose value is known to differ throughout history, between 3.5 and 15 kilometers, but the Jaina clearly must have used a value in that range (commonly thought to be 12 kilometers).

The Spiritual Meaning of (Almost) Zero

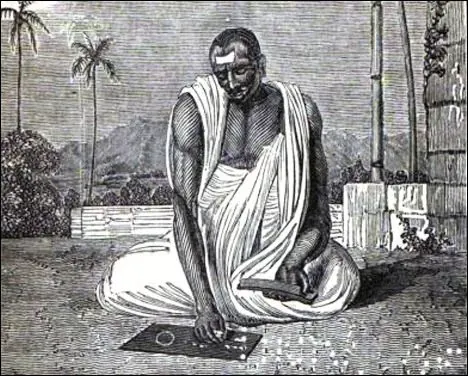

Working with huge numbers is not the only remarkable achievement of ancient Indian mathematics. You know surely that Brahmagupta, who lived in the seventh century CE, invented the symbol for zero. But he did more than that. In one of his treatises, Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta, written in 628, there’s the chapter titled Shunya Ganita (Computations with Zero), which introduces infinity and calls it kachheda. Etymology and Brahmagupta’s computations suggest that the original meaning is the result of division by zero.

Zero and infinity appear as interrelated mathematical quantities, but their connection is also spiritual. G. S. Pandey (see the References section) mentions the ancient text Katha Upanișad, composed between the fifth and the first century BCE. Therein, it is written that when a man makes their desires reach zero, they become immortal, hence divine and infinite.

Just like the Jaina wrote about very large numbers without calling them “infinite”, Bhāskara the Second (c. 1114-1185), a mathematician and astronomer, wrote about very small quantities. He defines subdivisions of time intervals like the nimesha (translated as “the blink of an eye”) with a rigorous method that makes it equal to 1/972,000 of a day. This has further subdivisions until you reach 1/2,916,000,000 of a day, which is called a truti.

As in the case of the Jaina teachings, I find unbelievable both the precision of such computations, and the determination not to call such quantities “negligible” or “almost zero”.

In Western civilizations, the million has Latin roots: the word mille has no clear origin, but it is known to be used by Latin speaking people to mean “very large”. The billion and its multiples appear after the Middle Ages and more precisely after the seventeenth century, when mathematics was already almost modern.

In the Eastern part of the world, around the year 1000 BCE, in Yajurveda Samhita, a book belonging to the collection of the Vedas, you find prefixes and multiples up to 1012 (trillions, in modern language), known as paradha. The list continues in other Vedas and scriptures, up to 10420, called asamkheya, translated as “innumerable”. Such multiples are taught by the Buddha and that last order of magnitude is characterized poetically as the number of raindrops that fall in all the worlds in ten thousand years.

In scriptural comments, European scholars focused more on qualitative and phenomenological analysis. For example, the Catholic priest John Duns Scotus wrote in a treatise of the thirteenth century about the continuous movement of angels, aiming to prove that their trajectory is indeed continuous in a mathematical sense.

Perhaps small numbers have symbolic meanings in many cultures because we are born with them on and around us, with 2 hands, 10 fingers, 10 toes, 2 eyes, 32 teeth. They have clearly influenced our numbering systems, timekeeping and more. But they could also have limited our numerical imagination.

I don’t know where most of the numbers in Jaina spirituality come from, but I find them fascinating through precision, let alone order of magnitude. I cannot read the original texts, and I couldn’t access academic references other than those I recommended below. Therefore, I would be very curious to find out more on the topic, so please leave a comment below if you have recommendations for me.

I am convinced that understanding mathematics and its creation by and in the human mind are universal pieces of knowledge which are greatly enriched by a wide perspective, both geographically, anthropologically, and chronologically.

References and Further Reading

- George G. Joseph – The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, 2011 (especially Chapter 8, on Ancient Indian Mathematics).

- G. S. Pandey – The Vedic Concept of Infinity and Infinitesimal System, chapter in History of the Mathematical Sciences, edited by Ivor Grattan-Guinness, 2004.

- Ian G. Pearce – Indian Mathematics – Redressing the balance, §Jainism available online here.

Thank you for reading The Gradient! The articles here will always be free. If you've read something useful or enjoy what we publish, please consider a small contribution by sharing on social media, starting a paid subscription, or a tip.